In 2018, we met with BAFTA winning documentary filmmaker, Victoria Mapplebeck to learn more about The Waiting Room, a multiplatform project which includes a smartphone short for The Guardian and a VR project funded by the ESPRC. The Waiting Room documents Victoria’s journey through breast cancer diagnosis and treatment. We caught up with Victoria a year on to find out more about her experience of developing her first ever VR project as she prepares to launch it into the public domain.

About the Waiting Room Film

When Victoria was diagnosed with breast cancer, she decided to record each step of her journey from diagnosis to recovery. Firstly, she began with a smartphone short, commissioned by Charlie Phillips, at The Guardian. Shot entirely on an iPhone X, Victoria filmed her time in waiting rooms, surgery, consultations, CT scans and chemotherapy. At home she filmed with her teenage son, as they came to terms with how family life was transformed by a year of living with cancer. The film sets out to document cancer from a patient’s point of view. “We have made cancer our enemy,” says Victoria, “a dark force to be fought by a relentlessly upbeat attitude. “Stay positive!” is the battle cry of the cancer patient. It’s a disease that favours slogans. ”Happy, Alive and Built to Survive”, “Cancer may have started the fight, but I will finish it” …The Waiting Room is the antidote to the tyranny of positive thinking. We will all encounter illness and death at some point in our lives, and yet we struggle to find the language to deal with it. This multi platform project begins with a personal journey but as cancer affects one in two of us over the course of a lifetime, it also tells a very universal story.” The Waiting Room smart phone short launches on The Guardian website in June 2019.

About the VR project

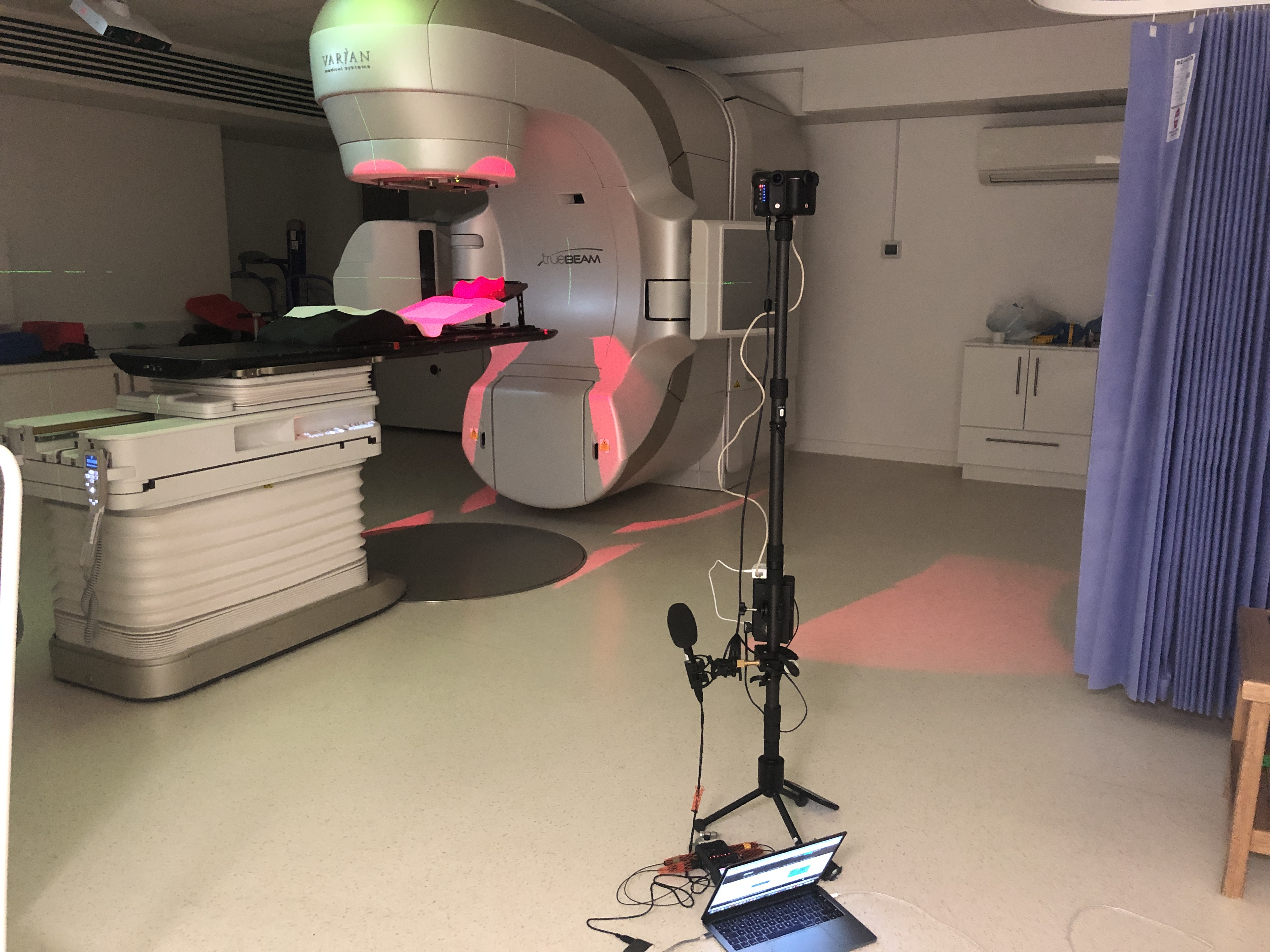

Victoria believes that creating a VR experience gave her a unique creative channel for her to tell her story. The Waiting Room: VR focuses more on the experience of cancer in a clinical setting , it explores the cultural myths and language of chronic illness, asking us to confront what we can and what we can’t control when our bodies fail us. The lynchpin of this VR piece is a 9 min durational 360 take, a reconstruction of Victoria’s last session of radiotherapy, which marked the end of nine months of breast cancer treatment.

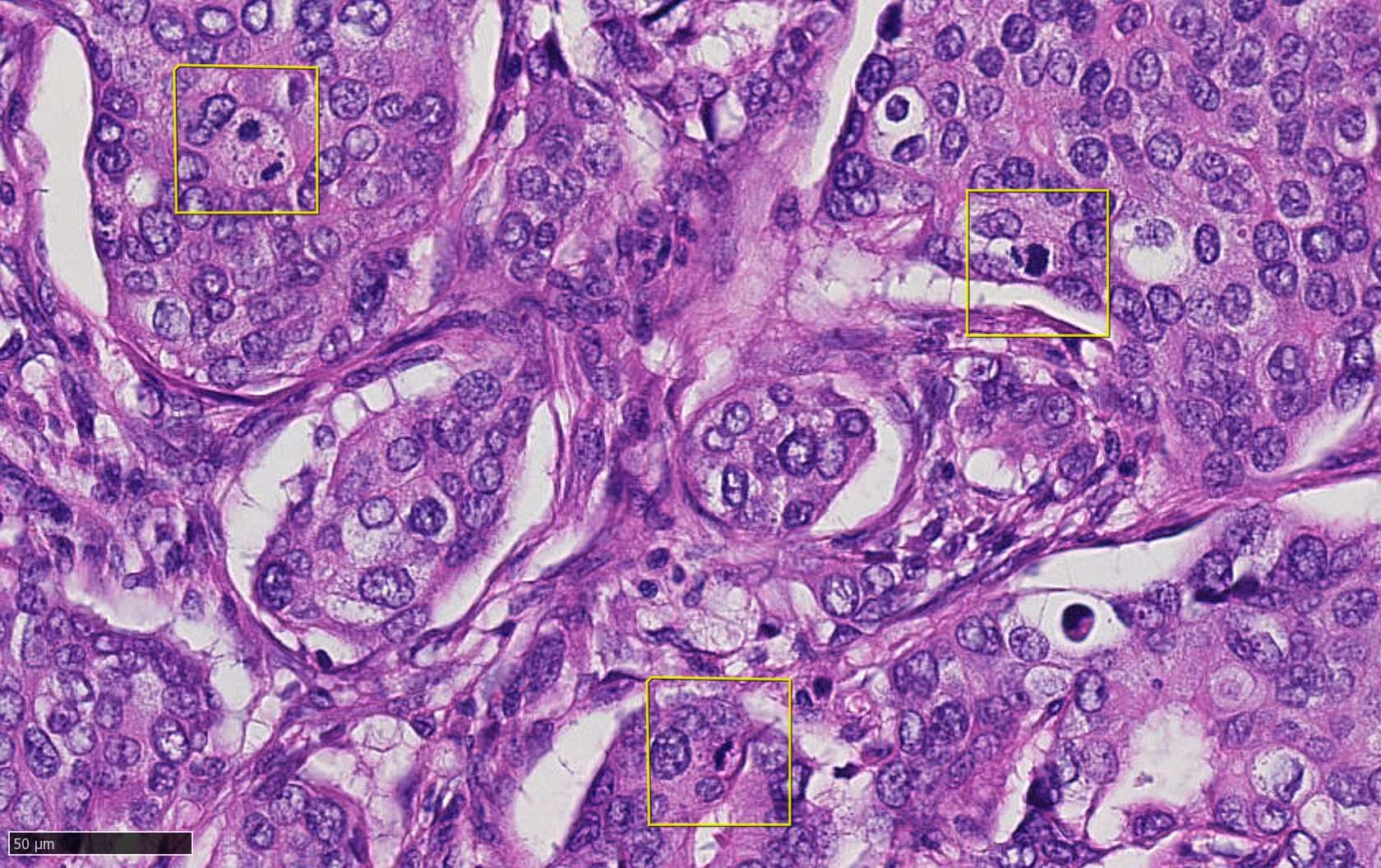

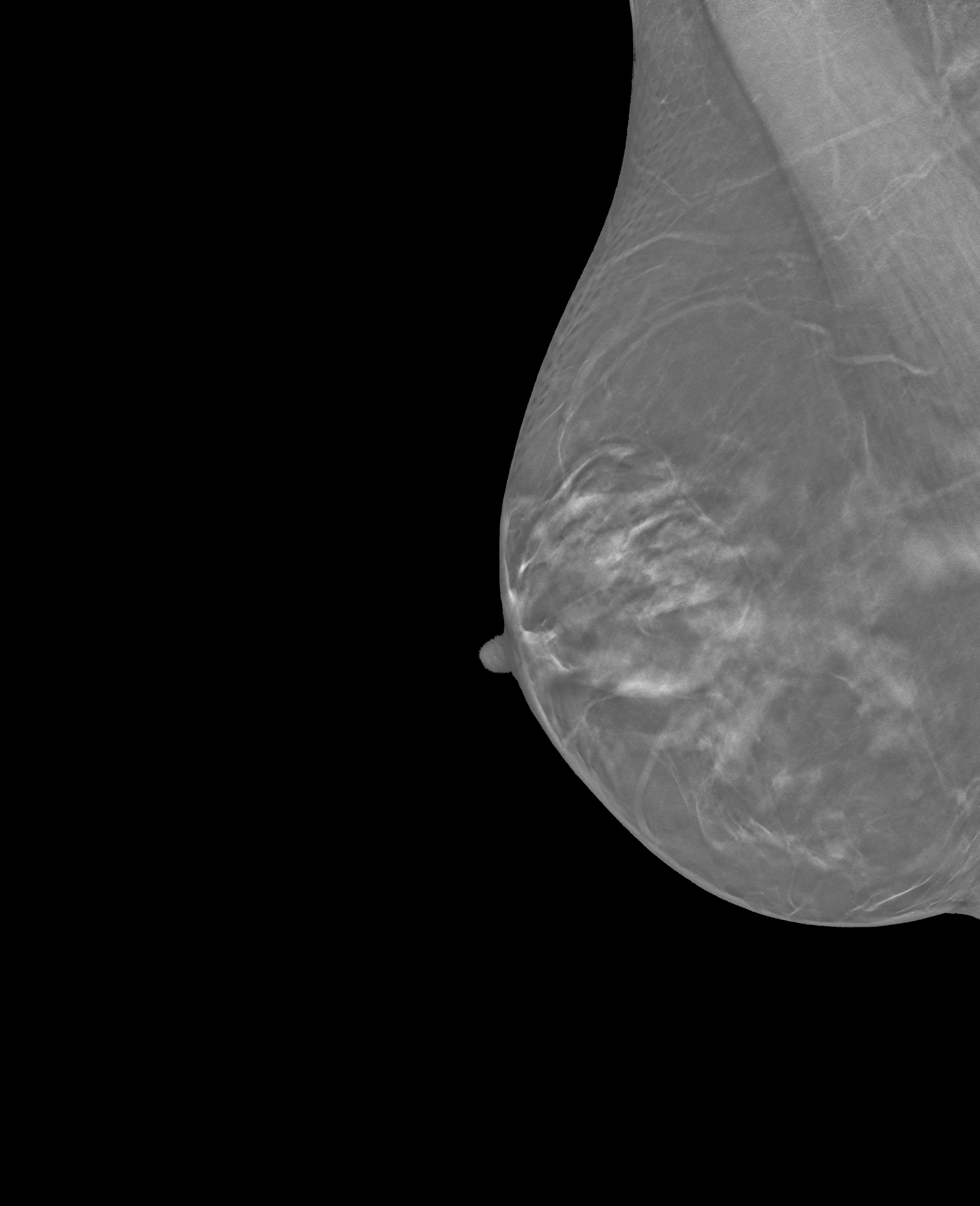

This experience is counter balanced by a CGI journey inside Victoria’s body. Working with 3D artists, Victoria has bought to life the medical imaging she’s collected through out treatment. Cancer cells, CT scans, mammograms and ultrasound provide a 3D portrait of her body from the inside, out. Victoria makes visible the often invisible parts of cancer treatment, the sickness, the fatigue, the tears and the hair loss. The soundscape is the driving force at the heart of the VR experience as it captures Victoria’s inner monologue and memories of her year of treatment throughout the piece.

Victoria has also experimented with a multi-sensory Vive version of the VR project. “Part of my radiotherapy treatment involved breathing in and out, to move my heart out of the way of the radiotherapy beams. This is a critical point in the experience. We are testing a piece of equipment in which the user is encouraged to breath in , in sync with my own breathing throughout the experience.”

Securing a Commission

In early 2019 Victoria won a commission from Virtual Realities, an ESPRC funded collaboration between the University of Bristol, University of Bath and UWE Bristol (the University of the West of England), in partnership with Watershed, BBC, the Guardian, Aardman Animations, VRCity, Jongsma + O’Neill, Archer’s Mark, VRTOV and MIT Open Documentary Lab.

The VR commission was key to the development of the project as it provided Victoria with both financial and creative support. As Victoria was one of two artists commissioned to work with VR for the first time, she gained a lot from the advice and support she received at each of the VR labs, feedback from key people, including Professor Mandy Rose, and peer support from fellow artist, Lisa Harewood, was invaluable. “The labs really nurtured an experimental approach the research and development period, in which each iteration of the piece explored and challenged the language of VR. The labs also really encouraged us to find our own individual voice as VR directors, and to find a more ‘process driven” way of exploring the form and feeling that we could be a key part of the production process,” explains Victoria.

Finding the right team

As telling such a personal story is the driving force behind the project, finding the right team to collaborate with was crucial to the successful development of the project. Victoria was clear that she needed to work with a creative team who brought not just the right technical skills, but were also in tune with her vision.

Finding the right CGI team was also essential, especially given it was the first time that Victoria had integrated spatial storytelling into her work. Victoria worked closely with executive producers, Darren Emerson from East City Films and Catherine Allen and Producer Shehani Fernando who has a wealth of non-fiction VR experience from her time at the in-house VR studio at The Guardian. Victoria also collaborated with creative technologist Luca Biada. “I had access to all my medical records from King’s Hospital, so all the images in the VR experience are taken from my body. The cancer cells are mine and because I had staging investigations, we were able to work with my CT scan. Using Unity, Luca put these images through volumetric capture to explore the CT scan in 3D. I was so lucky to work with amazing technologists throughout the experience.”

Capturing the right tone

Being Victoria’s first VR project, she faced a steep learning curve getting to grips with the challenges of a new creative channel. “There were some challenging times during production, capturing the right tone in representing such a personal and emotive experience was hard at times. On the Guardian film, I already had the skillset as a 2D filmmaker to know how to get it right, but with the VR project , that process of harnessing the look and feel of the final work was a steep learning curve, but ultimately a very rewarding one” . For Victoria, combining the CGI with the real time audio soundscape was the key to finding her own voice in this medium.

Technical challenges

Coming from a documentary filmmaking background, Victoria possesses transferable skills in both production and post production that can be applied to embrace immersive storytelling. But she still sees that many might be put off by a lack of specific technical skills, such as Unity or Unreal. Critically, this could be more of a barrier for women, as these technical roles are predominantly filled by men. Victoria has recently joined the steering group for Visions of Women in VR, an initiative aimed to address the gender imbalance the industry still faces. This initiative lead by Catherine Allen, Professor Sarah Atkinson and Helen Kennedy aims to create ‘a future where the immersive sector challenges the status quo of gender imbalance in creative industries and tech, seizing the opportunity to craft VR into an inclusive and healthy sector that learns from the mistakes of other media sectors’

Victoria also hopes that Reach, a Web VR platform created by Emblematic Group and VR pioneer Nonny de la Peña, offers another exciting development in helping to diversify VR. By removing some of the barriers to entry, Victoria is confident that tools such as Reach, will help make VR easier to create and consume.

Ethical challenges

With VR’s potential as an ‘empathy machine’, Victoria was mindful of the responsibility of putting the participant into such an emotionally raw experience. “I wanted to avoid users feeling as though they were the patient,” she explains. “I wanted them to experience my treatment as though they were a witness or companion; right by me and with me throughout my treatment. It’s quite a unique position to be in. For example, it was important that you can see my face, which stops it from feeling like a predominately embodied experience.” Victoria also highlights that for such an emotional piece, that trigger warnings in advance are crucial, to avoid any potential distress on the part of the participant.

The future of the Waiting Room

With the Waiting Room launching in June 2019, the film will be available via the Guardian website and will also be entered for international film festivals with the accompanying VR experience. But Victoria believes that it has a life beyond the festival circuit and is working closely with Catherine Allen from Limina Immersive on an outreach campaign which will bring the film and VR piece to hospitals and cancer centres throughout the UK in Breast Cancer Awareness Month in October.

For Victoria, the creative process of developing The Waiting Room has provided a way to help get through a challenging year. “Looking down the barrel of a microscope at my own cancer cells was a really life changing moment. Scrutinising my experience of cancer in such forensic detail has been liberating in some ways but I’m now ready to move on to new challenges. To transform my experience of cancer into something creative has really helped me,” she concludes. “Cancer hugely changes your identity, but I don’t want to be completely defined by it.”

Throughout this project, Victoria also sees that immersive technologies have a potential communications role to play in the treatment of cancer patients. “One of the worst parts of my cancer journey was not being fully prepared for some of the side effects of the treatments and medication I received. Seeing the pressures on NHS staff, VR could be used to help breast cancer patients prepare better for some of the challenges of their treatment and to feel as though they have more agency throughout the process,” she notes.

“It will be fascinating to see how The Waiting Room will be received by breast cancer patients and clinicians,” Victoria notes. When her own oncologist, Dr Anne Rigg experienced the film and VR project recently, she felt that it gave her a fuller and more in-depth insight into cancer from a patient’s point of view. “I would talk to Anne about the side effects of my treatment during our consultations but I think cancer patients sometimes feel an unwritten pressure to try and stay positive. The film and VR project, really expose the realities of cancer treatment for both patient and their families. Anne and I recently did a talk together at Sheffield Doc Fest in which she described The Waiting Room as an important resource for breast cancer patients and clinicians. It was really moving for me to feel that these creative works may have a real impact for the wider breast cancer community”.

Find out more about Victoria Mapplebeck’s work by visiting her website.